This is the second post where I take a look at Google NGram visualizations of the history of neuroscience. If you haven't seen

the first one, you probably should before continuing to read this one.

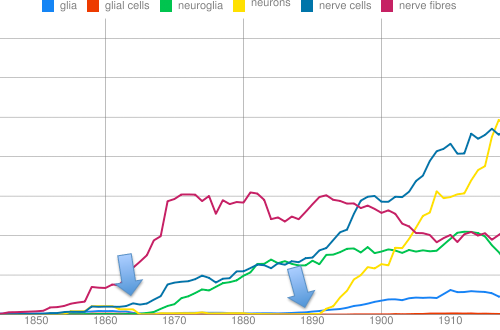

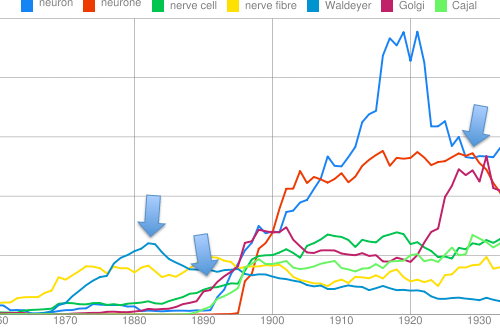

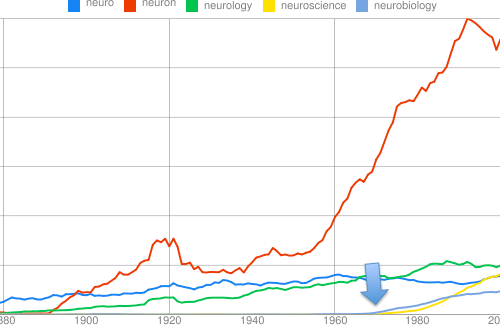

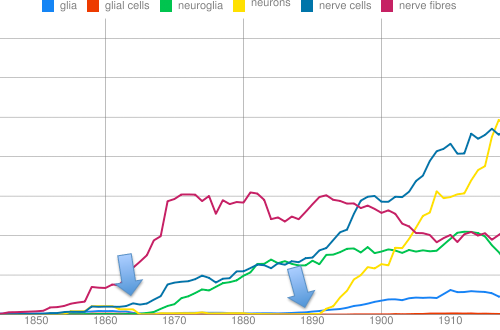

In my previous post I completely ignored a large number of the cells in the brain: glial cells! It's often said they outnumber neurons by a ratio of 10:1, a truth that is still open for modification, but at the very least in some brain regions they are just as many as the neurons. Let's plot some different general terms for these cells against the terms "neurons", "nerve cells" and "nerve fibres" as references. In plural just because I've already plotted the singular forms in the previous post.

We can see that mentions of "neuroglia" go back to roughly the same period as "nerve cells" and "nerve fibres", some 2-3 decades before "neurons". Around this time "neuroglia" was a general term referring to the "connective tissue" of the nervous system,

according to the OED, as opposed to the fibres which were considered the actual nervous tissue. The word neuroglia literally means "cement of the nerves". Nowadays it's known that they have so many other functions than providing support and nutrients for neurons, including very important modulations of signaling in the brain.

The use of simply "glia" starts taking off around the same time as "neuron", showing the co-incidence of the

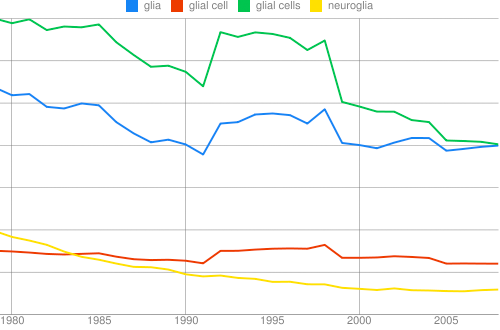

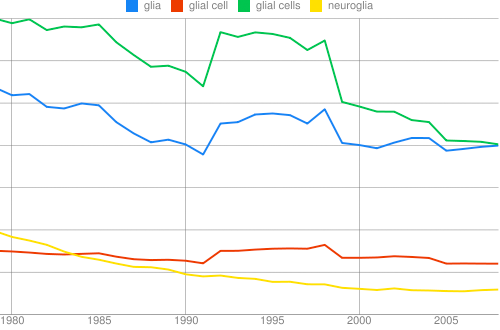

neuron doctrine and the characterization of the actual cells that made up this previously so vague "connective tissue". To find the first use of "glial cells", which is quite a common term nowadays, we have to fast forward to the 1940's and 50's. If you take a look at this following NGram there's some indication that both the plural "glial cells" and the singular "glial cell" are more commonly used than "neuroglia", but the differences are not very big.

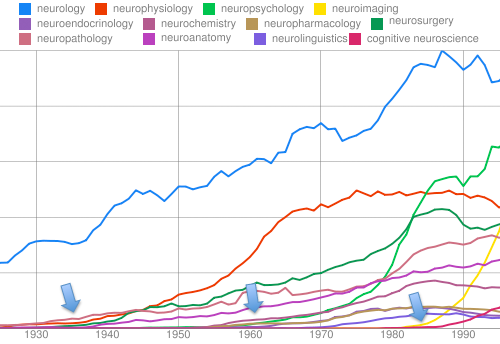

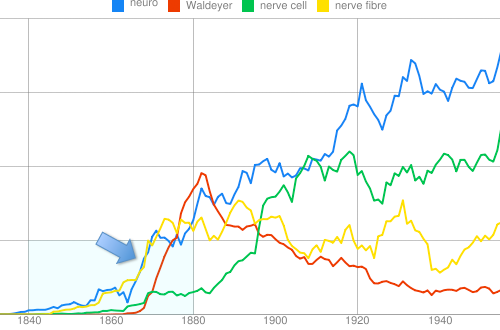

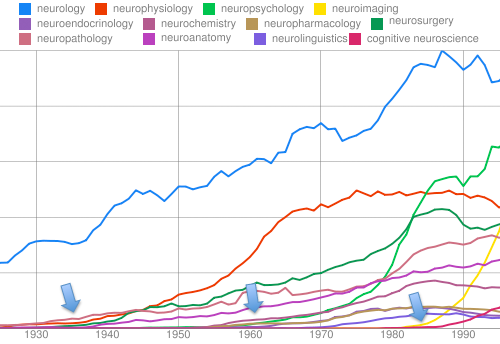

In my previous NGram post I plotted the more general terms "neurology, "neuroscience" and "neurobiology" against each other, but what if we add as many sub-fields of neuroscience and neurobiology as we can come up with to see it it's possible to see how the field has diversified and developed? I include "neurology" as well for reference.

I notice a couple of really interesting things instantly. First of all, "neurology" does seem to be the oldest term by far, and many of the more specialized terms seem to predate "neuroscience" and "neurobiology" as well (

see the first post). I propose that the diversification of the field seems to have happened in three "bursts" (arrows) during the 20th century! "Neuropathology" seems to be quite old, but together with "neurophysiology", "neurosurgery" and "neuroanatomy" it forms a cluster that starts going up during the 1930's. The second burst was during the mid 1950's to mid 1960's when "neurochemistry", neuropharmacology, "neuroendocrinology" and "neuropsychology" start going up (the latter two practically overlap). Sort of associated in time to this cluster is "neurolinguistics", that for some reason strikes me as a true child of the 70's.

The last burst is perhaps less certain, but we see the marked increase in the use of "neuroimaging" during the 1980's, showing the awesome technological development of the late 1900's. "Cognitive neuroscience" also forms part of this later burst and seems to be intimately associated with the rise of neuroimaging technologies. The NGram viewer wouldn't allow me to add more terms, but in

this ngram you can see that "neuroethology" has a small little bump around the same time.

It's remarkable how you can really read the development of the field, from an early focus on the "mechanics" and "physics" of the nervous system to a subsequent discovery of the chemistry of the brain, when else but in the 60's!, and a progressive realization that it affects our cognition and behaviors, paired with technological advances.

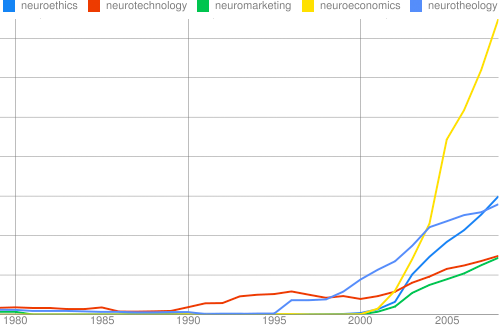

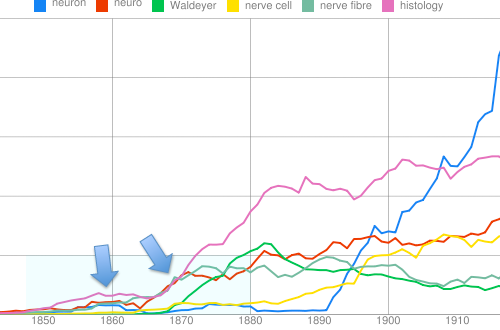

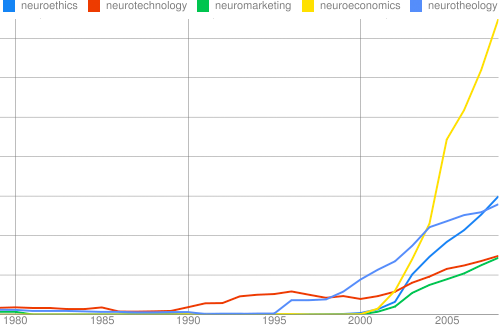

What are then the terms of the future? What are the neuro-terms on the rise? After doing several experiments, I came up with these: "neuroethics", "neurotechnology", "neuromarketing", "neuroeconomics" and "neurotheology".

"Neurotechnology" is not surprising. But perhaps what we're seeing here more than anything are the growing attempts to reconcile or explain questions of morality, spirituality and philosophy with neuroscience as well as a growing obsession with the cognitive and neurobiological processes behind money-making/spending. Seems like a weird and wonderful future.