A study published in PNAS last week (ahead of print) set out to examine which psychological "dimensions" make up religious belief and how the brain processes them, largely through the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging, fMRI - a technique that allows researchers to get images of brain activity in awake test subjects performing different tasks. In this case the task was agreeing or disagreeing with statements such as "God is removed from the world", God is punishing", "God is forgiving", "A source of creation exists", "Religion provides moral guiding" and so on.

Some interesting conclusions:

The practice of religious belief involves the assessment of god's perceived involvement in the world and god's perceived emotion. So when we ponder god, we use the same brain networks that are used for understanding the intent of people around us, understanding their emotional state, predicting their actions and generating an appropriate emotional response to give back. This is a central mechanism behind our social interactions. This study demonstrates that we think of gods just as we think of anyone around us. There are no particular parts of the brain that are dedicated explicitly to understanding god, instead our brains try to "read" god just as we read the people we interact with.

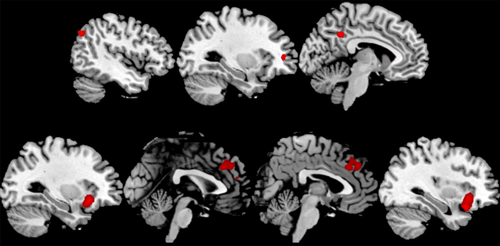

It also seems like the reason some people adopt religious beliefs while other don't is largely emotional, with the effect being larger for those who are believers. When religious test subjects were asked to actively deny a series of religious statements they showed much larger involvement of brain networks involved in the communication between emotions and cognitive processes than non-religious test subjects. You can see these brain regions in the lower row of the figure below. This finding will be familiar to any non-believers who have discussed religion with believers. Their final arguments are often emotional instead of logical, they often claim to "just know" and their position is motivated by the negative emotional response of considering a world without god.

Ref: D. Kapogiannis et. al. (see reference below)

I'll take the opportunity to recommend the blog where I first found this study: Epiphenom. It's updated frequently with a lot of very nice information from studies on the neuroscience and psychology behind religious belief. You can read more there. But while the author of that blog states that this study doesn't do anything to prove that religious belief is a by-product of evolution, I see that it absolutely does. The authors even conclude with:

The evolution of these networks was likely driven by their primary roles in social cognition, language, and logical reasoning. Religious cognition likely emerged as a unique combination of these several evolutionarily important cognitive processes.

To me it's pretty clear that any supernatural belief is an "overshoot" of mental capacities that we use for other purposes, that we relate to supernatural entities just as we relate to those entities we interact with. Whether this is adaptive or not, whether it's been to our advantage or not, is another question altogether. I'm inclined to believe that given the complexity of the brain and the complexity of phenomena it can generate, it's unlikely that all of them, at any point in evolution, are the result of adaptation. The brain simply does too much. I'm open to the thought that cultural phenomena could have "abducted" some of our cognitive abilities more or less "by accident" to generate some of the more colorful phenomena of our cognition and behavior.

Kapogiannis, D., Barbey, A., Su, M., Zamboni, G., Krueger, F., & Grafman, J. (2009). Cognitive and neural foundations of religious belief Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0811717106

Swedish blog tags: Vetenskap, Biologi, Neurovetenskap, Hjärnan, Religion

Technorati tags: Science, Biology, Neuroscience, Brain, Religion

I have not read the article but trusting in your summary:

ReplyDeleteI think it’s very interesting how people use the same areas of the brain to interact with God as with other people, which might be due to the “humanized” image we have of him, at least within Christianity. I wonder if it is the same for cultures having animals or astronomical objects as gods.

I do not agree that the reason to be religious is emotional. The fact that religious subjects showed larger involvement of brain networks involved in emotions than non-religious subjects after God-denying arguments, or the visible negative emotion generated in believers, it is just as simple as understand i.e. why the mother of a Down Syndrome kid is hurt when someone disparagingly tells her his kid is a retarded or he suffers any kind of discrimination. It is the so much high importance that God has for believers that it makes a sensitive subject; it is considered as sacred as your more beloved person. Why? There are no logical reasons for faith.

Uy ahora puedes ver mi vieeejo blog, ignóralo, parece de adolescente.

ReplyDeleteDaniel, I agree that it's clear that religious beliefs 'co-opt' brain structures evolved for other purposes. The question is whether religious belief is a necessary, and fitness-free, consequence of those brain structures. Or whether the specifics of how those brain structures work has been modified so as to favour religion (perhaps because religion offers an adaptive advantage).

ReplyDeleteWhat this study shows is that we don't have a special 'god-spot' - but it doesn't demonstrate that brain architecture hasn't been modified in more subtle ways.

(PS thanks for the link!)

Angélica: Ja! Ya lo había visto hace rato. Cuando conozco una persona nueva lo primero que hago es buscarla en Google. :P

ReplyDelete"I think it’s very interesting how people use the same areas of the brain to interact with God as with other people, which might be due to the “humanized” image we have of him, at least within Christianity."

They do mention in the article that it's definitely worth looking in test subjects of other religious beliefs, but I don't think it has something to do with a humanized vision of god. Our brains are just as ready to "incorrectly" ascribe intentionality to animals, machines and even meteorological phenomena. In our minds the reasoning behind the statements "god wants you to be a good person" is no different than "the printer wants you to put in more paper".

"I do not agree that the reason to be religious is emotional..."

I accept everything you wrote, no problem. They mention exactly that in the article. Being religious and denying your faith is associated with feelings of guilt and so on, feelings that non-believes don't have to deal with in the same situation. But why wouldn't it indicate an emotional motivation for religious belief that there's a similar emotional motivation for loving your disabled child? On the contrary.

The point I made was that religious people often make emotional arguments for their faith, not because there is a lack of logical arguments, but because their faith is emotionally motivated to begin with. The parts of the brain that became activated were largely those that generate a deep emotional response to cognitive conflict, not those that process knowledge or memory or linguistic abilities.

There are actually quite a few logical arguments that people have tried to make for the existence of a god or to defend their faith. So it's possible. None of them are very good, but it shows we can use our "logical centra" in the brain to at least try to understand things that don't necessarily have a reasonable explanation.

I think it speaks volumes about the nature of religious belief that there is an emotional reaction when denying a statement of your faith. That doesn't mean emotional reactions to cognitive conflicts are only limited to religious belief of course. That's precisely the point of these findings. It's significant that denying your faith is similar to someone offending something that touches your personally. It means that becoming religious and accepting a faith is a process that stimulates your emotions more than your logic or your knowledge, that gaining conviction is an emotional process and that when defending or justifying religious faith our brains are heavily affected by emotion.

It's reasonable to think that those of us that haven't been brought up to experience strong emotional reactions to religion are less likely to be believers.

Tom: Cheers! I read Epiphenom quite often and I'm only happy to recommend it.

I'm a bit resistant to limit the scope of this study to just determining that we don't have a specialized brain structure to believe in higher powers. There really is no reason there should be one and it wouldn't be reasonable to expect one. Although it's of course interesting that they've mapped which regions are involved.

I agree that the question about whether it's adaptive or not is a separate one, and I've detailed by opinion above. However, I think that the findings absolutely make it possible to make the argument that religious belief is nothing more than a non-adaptive (not necessarily maladaptive) secondary effect of regular cognitive processes. It's not definitive evidence of course, but considering what we now know I think that the opposite scenario would be far more unlikely: that once we'd acquired religious belief it would have somehow been beneficial to our general cognitive skills and thus religion would have been selected for.

Still when it comes down to it, I'm reluctant to take an obligate adaptationist view of the matter. It might not be a necessary and "unavoidable" consequence of our regular cognitive abilities, but it's definitely secondary to it in my opinion.

I am a doctoral student in cognitive science studying memory at a more psychological level and so neurological research is often beyond my understanding. While I find this article very interesting and a lot of your points are well founded there is one thing I wonder about. It seems that you are arguing for emotion to be a causal mechanism when all that has been demonstrated here is a correlational relationship. The logical conclusion of emotion as a causal mechanism for religious belief is not entailed here.

ReplyDeleteI recognize fully that I may be grossly misunderstanding your argument but I find that many causal conclusions from neurological and psychological experiments are confounded by only observing correlations and not controlling for causation. The logic behind causal interpretations is very fickle and in my opinion, should be tread upon with great care.

Despite this, I think you offer some great insights here. Thanks for the post.

Thanks for the comment.

ReplyDeleteI'll admit that most of what I wrote about emotional motivation for religiosity is pure speculation on my behalf - while still remembering that religious behavior isn't just one thing and is likely to have a number of underlying causes.

What they observed in the study was that the cognitive conflict it entailed for a religious person to reject religious statements involved more emotional centra in the brain (anterior insulae and middle cingulate gyri) vs. non-religious people. I interpret this as the likely result of an emotional component in the motivation behind the individual's religiosity. But I'm ready to admit it's pure conjecture if I'm presented with the proper evidence against it.

What I wrote in the above comment was more defending the view that emotions could be a significant contributor to religiosity, not that it necessarily had to be or that it was supported by the study.

great blog

ReplyDelete