I've written before

I've written before about how religious beliefs probably are grounded in brain mechanisms that we use for other purposes, primarily social interactions. There is no "god spot" in the brain, rather we think of supernatural all-powerful agents much in the same way as we think of the people we interact with. It suggests that religious belief is a secondary effect of basic or general mechanisms that guide social cognition, although it is not definitely proven.

That study dealt with god's perceived involvement in the world and god's perceived emotion among other things - in a newer article published around christmas in PNAS a team of researchers have investigated how believers think when they think about

god's will and god's own beliefs. The importance of such an investigation is highlighted already in the opening paragraph of the article.

Religion appears to serve as a moral compass for the vast majority of people around the world. It informs whether same-sex marriage is love or sin, whether war is an act of security or of terror, and whether abortion rights represent personal liberty or permission to murder. Many religions are centered on a god (or gods) that has beliefs and intentions, with adherents encouraged to follow "God’s will" on everything from martyr-dom to career planning to voting. Within these religious systems, how do people know what their god wills?

Since we already readily infer other people's beliefs egocentrically, that is as similar to our own - conservative people tend to gauge positively evaluated people as more conservative than progressive people do - it's justified to ask: How do your own beliefs guide your predictions about god's beliefs? Especially since we seem to think about god as we think about the people we interact with. According to these results believers project their own values and beliefs on their god (or gods) to a great extent, which could certainly help explain not only the great diversity and variability of religious belief and expression, but also the ambiguous nature of religious interpretation.

The paper includes several studies, among them several correlational studies using surveys where people were asked to estimate god's, the "average American's", Bill Gates', George Bush's (among other known figures) beliefs on several controversial subjects such as abortion and same-sex marriage, and an experimental study where the subjects' beliefs were manipulated through exposure to persuasive arguments in order to see if they "changed god's mind" as readily as they changed their own.

Most interestingly for me though, they also conducted a neuroimaging study, and since it's what I'm most familiar with I will focus on that. It consisted of 17 test subjects reporting their own attitudes on controversial subjects as exemplified above, as well as estimating the attitudes of the "average American" and god on the same subjects while in an MRI machine.

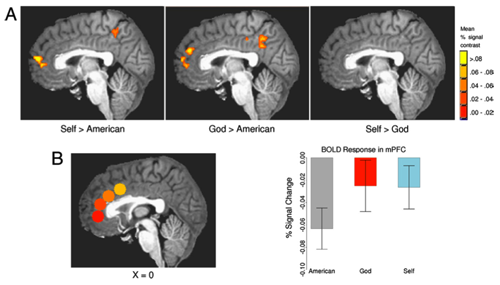

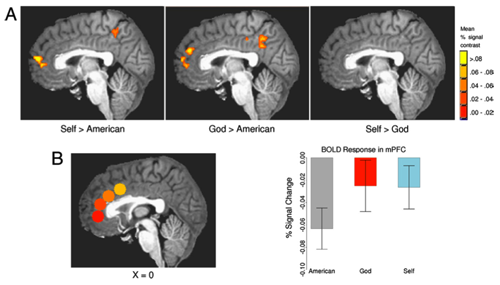

Below you see three images that highlight the

differences in brain region activation (yellow/orange spots) when comparing the measurements done while stating your own attitudes vs. estimation of the "average American" attitude, estimation of God's attitude vs. the "average American" attitude, and most interestingly your own attitude vs. estimation of god's attitude.

Ref: N. Epley et. al. (see reference below)

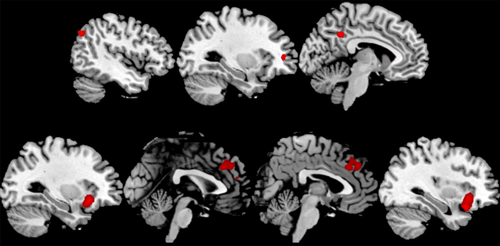

Ref: N. Epley et. al. (see reference below)

As you can see, there is no difference between thinking of your own beliefs and thinking about god's beliefs, which stands in contrast with how it looks when you're thinking of another person's beliefs. Of course the image only shows one representative slice of the data, but the results were consistent across the panel. Thinking about god's beliefs seems statistically indistinguishable from thinking about your own beliefs, whatever your beliefs are.

The brain regions that were found to show differences in the self vs. American and god vs. American comparisons, and no differences is the self vs. god comparisons, include regions that are known to be involved in thinking about your own mental state and in the projection of your own mental states onto others. In a follow-up analysis the authors closed in on one of these regions, the medial prefrontal cortex, and observed that it had a significantly lower activity when thinking about the beliefs of the "average American" than when thinking of your own beliefs or those of god, which again were indistinguishable. Compare the three columns in figure B. BOLD is the measurement of blood oxygen level in the brain regions, which is a correlate of brain activity.

There is a growing body of literature showing that religious beliefs seem to emerge from the same neural substrates that produce a more general social cognition. The interesting point in these studies is that while we relate to the entity of god and experience god's involvement in the world much like we would that of another person, our estimations of god's will and beliefs are self-referential and egocentrically biased, more so than our estimation of other people's beliefs. Religiously motivated political, moral or social stances may originate just as much from your self as from others in your surroundings, like your parents or congregation. Indeed it only seems natural to assume that god has the same belief as oneself. God, as the supreme authority, must hold true beliefs and most people naturally presume that their own beliefs are true.

As an atheist one is often confronted with the view that without religion there would be no morality; that without religion humanity would degenerate. As a professed nonbeliever you're either an immoral degenerate or unconsciously religious. These data provide some evidence that morality and personal beliefs are native to human cognition and are largely independent from religious inputs.

People may use religious agents as a moral compass, forming impressions and making decisions based on what they presume God as the ultimate moral authority would believe or want. The central feature of a compass, however, is that it points north no matter what direction a person is facing. This research suggests that, unlike an actual compass, inferences about God's beliefs may instead point people further in whatever direction they are already facing.

PS: Just as a side note I want to mention that in one of the correlational studies they included nonbelievers. However the results were difficult to interpret. Nonbelievers seem to go less according to their own beliefs when estimating god's beliefs... which somehow makes sense but kind of doesn't prove anything. At least, the authors note, it demonstrates that you have to believe in god to make an egocentric estimation of god's beliefs in the first place.

Epley N, Converse BA, Delbosc A, Monteleone GA, & Cacioppo JT (2009). Believers' estimates of God's beliefs are more egocentric than estimates of other people's beliefs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106 (51), 21533-8 PMID: 19955414

Swedish blog tags: Vetenskap, Biologi, Neurovetenskap, Hjärnan, Religion

Technorati tags: Science, Biology, Neuroscience, Brain, Religion