Within this context, I want to use as an example a newly published study in PNAS that links the actions of the neurotransmitter and hormone oxytocin to ethnocentrism – the tendency to view one’s own group, the in-group, as more important or superior to other groups.

Molecular structure of

Perhaps more than any other hormone, oxytocin has become the perfect example of the kind of “hormonal determinism” that I mention above: no doubt because the study of oxytocin is a very active field and because it’s been linked to some very fascinating behaviors. Doing a quick search for oxytocin at ResearchBlogging.org, for instance, is a good way to start finding evidence of this. Oxytocin has been linked to trust and cooperation, generosity, facial recognition and emotional context, social bonding (with interesting implications for autism), learning and memory in social situations, empathy, parenting styles and maternal bonding, sexual arousal, ejaculation and orgasm.

In the present study by De Dreu with co-workers, published in the advance edition of PNAS (see reference 1 below), randomized test subjects were given nasal sprays with oxytocin or placebo and were then asked to complete computerized tests designed to reveal favoritism towards the own group (Dutch males in this study) and derogation towards people outside the own group (“Arabs” and Germans in this study). The results from these tests consistently indicate that those test subjects who were given oxytocin were more likely to favor their own group than those subjects who received a placebo; they were faster to associate positive value words to their own group, represented by Dutch names in one of the tests, and less likely to sacrifice a Dutch-sounding individual in order to save a group of nondescript people in a moral choice dilemma task of the “sacrifice one person to save several people”-type. However, there was only limited evidence for the idea that the giving them oxytocin influenced out-group derogation, or the attitude that the out-group is inferior to one’s own group. In other words, those subjects who received oxytocin were more likely to have ethnocentric attitudes, no matter who was in the out-group. This confirms earlier findings from the same research team (see reference 2 below) that showed that oxytocin could be implicated in in-group altruism, the willingness to do something that is detrimental to yourself but beneficial for your in-group, and defensive, but not offensive, attitudes towards out-groups.

The authors argue:

Results show that oxytocin creates intergroup bias because it motivates in-group favoritism and, in some cases, out-group derogation. These findings provide evidence for the idea that neurobiological mechanisms in general, and oxytocinergic systems in particular, evolved to sustain and facilitate within-group coordination and cooperation.

Elsewhere they write the following, speaking explicitly about racism and racial conflict:

Through its influence on in-group favoritism, oxytocin contributes to the development of inter-group bias and preferential treatment of in-group over out-group members. Because such unfair treatment triggers negative emotions, violent protests and aggression among disfavored and excluded individuals, by stimulation in-group favoritism, brain oxytocin may trigger a chain reaction towards intense between-group conflict.

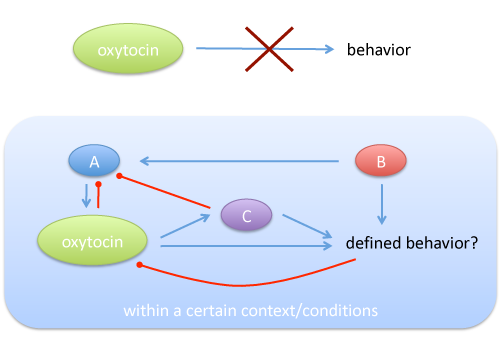

I see several problems with these conclusions. Firstly, notice how the language is used to give a very clear causative image: “oxytocin creates”, “it motivates”, “oxytocin contributes”, “oxytocin may trigger”. To give you an example: I counted nine instances of “oxytocin creates”, and eight instances each of “oxytocin motivates” and “oxytocin promotes”, or variations thereof, in the article. This use of language rests on "hormonal determinism" - the assumption that there is a direct causal link between oxytocin and the ethnocentric behaviors they observe, something they haven’t really proven in my opinion. But if there is absolutely no “hormonal determinism”, no direct causation between the actions of a hormone and a specific behavior - and let’s just for the moment assume that there is absolutely none, zip, zero – then how can we best interpret the repeated findings that clearly show that hormones are implicated in moods and behaviors?

The answer lies in the complexity of neurobiological systems. It’s possible to say that oxytocin is implicated in ethocentrism, but it’s difficult to say exactly under which conditions or in which situations outside of these experiments, or if it sometimes is overridden or reinforced by other neural substrates. The brain is complex enough to make it safe to assume that oxytocin probably isn’t acting alone. Therefore we cannot always trust that the statistical significance of experiments actually equals biological relevance. Especially when trying to draw any sort of evolutionary conclusions. These are tests designed to be very specific, to dissect out very specific behaviors out of the confounding factors. It’s good scientific methodology, as long as the conclusions match, which they don’t quite do in this case.

The difference between direct causal effect (upper) and complex neurobiological regulation (lower). The latter is entirely hypothetical in this case, but you get the picture. Blue arrows indicate positive regulation and red pointers inhibition. Many different factors can interplay and give feedback on different levels in order to produce a behavior.

So is there any good argument to say that oxytocin underlies racism, at least to some extent? Yes, sort of, to some extent. The authors of the study seem convinced of a direct causal link judging by the explicit mentions of racial conflict and the general tone of the article. In the abstract of the article they write “we conjecture that ethnocentrism may be modulated by brain oxytocin, a peptide shown to promote cooperation among in-group members.”. But I’m less ready to take it that far. It’s not yet known which other systems are involved interacting with oxytocin and under which cultural/societal conditions they are “switched on” (see figure above).

Several of the articles and blog posts that have covered these findings have pointed out that this reveals the “dark side” of oxytocin, thus seemingly promoting a more balanced view of this hormone’s functions. Here in Sweden the headline frustratingly read: “Love hormone is also racist hormone”, while the New York Times and TIME Magazine have far more weighed articles where you can read more about the quite fascinating experimental methods.

It’s good that we get a critical look at the boundaries of these “cuddly” properties, but it’s justified to ask how “hormonal determinism” and the erroneous public perception of oxytocin as a “love hormone” are helped or balanced by the equally erroneous perception of it as a “racism hormone”. There is just as little motivation to call oxytocin a “racism hormone” based on these results as there is calling it a “love hormone” based on its “cuddly” properties. Also, our definition of racism or ethnocentrism may very well be arbitrary to a certain degree and not reflect the true situations that our brains have evolved in. But that is the subject of another blog post on another day.

(1) De Dreu, C., Greer, L., Van Kleef, G., Shalvi, S., & Handgraaf, M. (2011). Oxytocin promotes human ethnocentrism Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1015316108

(2) De Dreu, C., Greer, L., Handgraaf, M., Shalvi, S., Van Kleef, G., Baas, M., Ten Velden, F., Van Dijk, E., & Feith, S. (2010). The Neuropeptide Oxytocin Regulates Parochial Altruism in Intergroup Conflict Among Humans Science, 328 (5984), 1408-1411 DOI: 10.1126/science.1189047

>> Update February 1: This article is delayed a few days since my internet connection at home has been on the fritz lately and I didn't notice it didn't upload before the weekend.

>> February 2: Edited for grammar and punctuation.

Showing the varied and limited nature of complex variables in predicting behavior is really helpful. Let's hope people read it and put it to use.

ReplyDeleteAnd aside from the indirect and mediating roles the variables play, we've also got to keep in mind that the effects are likely small - because most behavioral effects are small. It's not like any one variable is the be-all-end-all of predictors.

Or, so this is a blog post on distinction between "creates" and "is implicated in". How fascinating!

ReplyDeleteYes, if you either choose to ignore or fail to understand most of what I wrote, in essence it's a post about the distinction between "creates" and "is implicated in". Let me try to make my point clearer.

ReplyDeleteThe former gives the wrong idea about the underlying biology. A lot of people, if you see the reports in the media and are in-tuned with public perceptions, think it's basically "add hormone, get behavior". But it's not only in the general public, just see how this hormonal determinism has affected the way these researchers make their arguments. This has far-reaching negative consequences for how we see the actions of hormones. The latter not only gives the correct view of hormones and behavior and how the brain works, but it also opens up for so many more fascinating questions. What other neurobiological factors are involved except oxytocin? How do they interact? In which conditions? Et c. It's simply good science.

I for one think it's a shame that there are a lot of people walking around having the wrong idea about a very important aspect of their biology. You might think otherwise. Like... the dissemination of scientific thinking and the public understanding of science, pffff BORING, like who cares, right?

You are not disseminating anything. You are pointlessly splitting hairs. Or mentally masturbating. Depending on one's point of view. Your post can be a template for any question in biology and sums up as "life is complicated". Duh.

ReplyDeleteWell, obviously I don't think it's splitting hairs, but I've made my point already. I think there are several interesting questions there, you obviously don't. That's fine. If it stopped at "life is complicated", I would agree with you, but I try to get something going about some specific ways in which life can be complicated.

ReplyDeleteI do hope that other readers of this post consider my points in a bit more detail than just "it's complicated" or beyond getting annoyed over semantics. I'm not interested in the language in itself, but in the underlying assumptions that lead to a certain use of language.

Everybody should use the words "tends to" more.

ReplyDeleteStill, people are open to the idea of hormonal influences on behavior in part because lots of celebrities have taken male hormones and people notice how they were before and during: Andrew Sullivan wrote 7000 words about how his testosterone injections have changed him in the NYT, for example. The effects aren't the same on everybody, but they obviously tend to point in certain directions.

Keep up the good work Daniel. Some people prefer the simple story. Mr God did it. Genes are responsible for it. It's her hormones. Chemistry is important but not on many minds. And then there are the simple chemistry stories that big pharma tends to promote when it has something to sell... The 7 Feb Nature Magazine has an article decrying the end of overt gender discrimination that isn't worth reading except for the 8 comments by women that skewer it. Seems science sometimes prefers the simple story over the hard truth of STEM discrimination.

ReplyDeleteQuick comment on ethnocentrism : that term specifically deals with ethnic/cultural groups, and the original paper argued that it was not only identification by ethnicity, but any sort of in/out group. I think that's an important point to be made here, otherwise people may try to link this specifically to issues of race and all sorts of other problematic things. It could just as easily be 'members of my soccer team' or 'my girl scout troop'.

ReplyDelete@ethnohistorian: Thanks for commenting. I agree completely, that's why I was surprised when the authors make racial conflict specifically the "angle" of the story they want to tell. The experimental setup is set up as a racial conflict. To be fair though, elsewhere De Dreu has brought up other in-group-out-group conflict scenarios.

ReplyDeleteDaniel, I could not agree more with your review. Science should be about finding the truth (and the truth is often not a direct cause-effect) instead of the search for recognition in the public/academia eyes.

ReplyDeleteAnonymous, thanks for the reference. The comments on that (weak) article from Nature are quite good and to the point. I think the comments should be the article ;)

Great read. Well done.

ReplyDelete