Einstein's brain was photographed only hours after his death. Ref: Falk (see reference below)

With that in mind, today I came upon a recent commentary on a study of Albert Einstein's brain published in Frontiers in Neuroscience last year. This re-analysis of the surface features of Einstein's cerebral cortex, using tools from the field of paleoanthropology, lead anthropologist Dean Falk to make new observations about Einstein's brain and the relation they might have had to his exceptional capabilities.

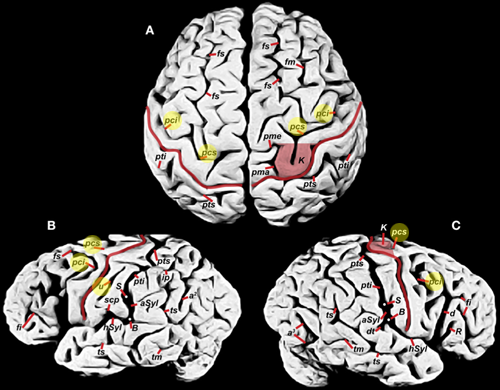

Falk closely analyzed photographs of Einstein’s brain that were taken within the first few hours of his death. These calibrated photographs, along with direct caliper measurements were the primary materials Falk used to reanalyze Einstein’s brain. Two identifications, a long, unnamed sulcus (u), and a knob (K), are the emphasis of Falk’s research because they are both unusual and uncommon.

<...>

One of Falk’s most groundbreaking findings is the presence of continuous precentral superior and inferior sulci (pcs and pci). These are present on both right and left hemispheres of Einstein’s brain; symmetry not found in 98% of the 50 hemispheres scored by Ono et al.

I've highlighted some of the structures in the image above in yellow since they're not very obvious in the original. Sulci (sing. sulcus) are the grooves in the cerebral surface and gyri (sing. gyrus) are the ridges.

This re-analysis also focused on areas that had been studied before. In particular areas on the lateral parietal and temporal lobes that are involved in the understanding and production of language. Einstein's brain has been the object of study for a long time and if you're interested in the history of this research I recommend you read the original article (see reference below). The general conclusion is that Einstein had several rare features that indicate a very special brain development with regard to how several areas around his primary motor and sensory cortex, as well as his lateral parietal and temporal lobes were organized.

Einstein’s brain was characterized by an unusual mixture of symmetrical and asymmetrical features. A rare convergence of the postcentral sulcus with the Sylvian fissure occurred bilaterally in Einstein’s brain, which nonetheless manifested a marked degree of asymmetry in the width of the lateral postcentral gyrus that favored the left hemisphere, and a pronounced knob in the right hemisphere. These asymmetries together with an atypical lack of uniformity in the medial and lateral widths of the pre-and post central sulci indicate that the gross anatomy of Albert Einstein’s brain in and around the primary somatosensory and motor cortices was, indeed, unusual.

Some of this unusual symmetry, but also the so called "knob" (K), which is on the area controlling the left hand, can possibly be related to Einstein's violin training and musical abilities as they would have required him to increase his dexterity with his left hand as well as his right hand. If this is true, the young Einstein's musical training left a clear mark on his brain. Some of the same features have been observed when studying the brains of musicians. The diverging organization of some of the areas involved in language could be behind Einstein's reported language difficulties - legend says he didn't say a word until the age of four, and then suddenly spoke in full sentences. Other reports say that he would often repeat sentences to himself until the age of seven. What's even more interesting is that they could possibly also be behind his mathematical genius and unique mind.

As an adult, Einstein famously observed that ‘the words or the language, as they are written or spoken, do not seem to play any role in my mechanism of thought. The psychical entities which seem to serve as elements in thought are certain signs and more or less clear images which can be ‘voluntarily’ reproduced and combined’. Einstein laughed when informed that many people always think in words, and emphasized that concepts became meaningful for him ‘only through their connection with sense-experiences’.

It's thrilling to consider that this may have affected the way Einstein reasoned and the way he saw mathematics and physics problems, although this is of course very speculative. It also tempts the imagination to think that his musical training as a boy might have, in combination, also contributed to his genius by stimulating his synthetic and analytical thinking. Einstein reportedly often played the violin when stuck on a particular problem. In such case, one could defend the argument that geniuses aren't born, but rather made. At the very least, the study of his brain shows the importance of the developmental processes that happen during childhood and youth for the establishment of, possibly exceptional, brain architectures. What you do with your brain during your life probably makes more of a difference than your genes. Like I wrote in the beginning of this post: It's less about how much you have and more about what you do with it.

Spicer, K. (2010). An old brain with new tricks Frontiers in Neuroscience, 4 DOI: 10.3389/fnins.2010.00040

Falk, D. (2009). New information about Albert Einstein's Brain Frontiers in Evolutionary Neuroscience, 1 DOI: 10.3389/neuro.18.003.2009

"legend says he didn't say a word until the age of four, and then suddenly spoke in full sentences."

ReplyDeleteThis legend is almost certainly false.

From a letter in the Einstein Archives written by his grandmother Jette, when Einstein was two years and three months, after visiting the Einsteins: "He was so good and dear and we talk again and again about his droll ideas" (Denis Brian, *Einstein: A Life*, p. 1, ref. given).

Einstein's sister records (presumably from her parents): "When the 2½-year-old was told of the arrival of a little sister with whom he could play, he imagined a kind of toy, for at the sight of this new creature he asked, with great disappointment, 'Yes, but where are its wheels?'." (A. E. Collected Papers, Vol. 1 (English language edition), p. xviii)

That is very interesting. I couldn't help including the legend as I had heard it because part of the fun about Einstein for me is that there is so much lore around his person. Thanks for the comment.

ReplyDeleteDo you know what the author of the article could possibly mean when he refers to Einsteins "well known delay at acquiring language and the fact that he repeated sentences to himself slowly until the age of about seven"? The reference he gives for that statement is this article: http://www.albert-einstein.org/article_handicap.html, where it says "Einstein himself told his biographer, Carl Seelig, that “my parents were worried because I started to talk comparatively late, and they consulted a doctor because of it.”" Is it all an exaggeration or is there any substance to the claim that he started talking abnormally late?

October 29 2010

ReplyDeleteDaniel: Sorry about the delay in responding. I've been busy and have only just seen your comments.

Thanks for giving the link to the article at the Albert Einstein Archives website. With reference to Einstein's "well-known delay at acquiring language", the most cited evidence comes from his younger sister Maja's biographical sketch written in the early 1920s. It is from her that the report of the infant Einstein's remark "but where are its wheels" comes. She writes that "his early thoroughness in thinking also found a characteristic, if strange, expression. Every sentence he uttered… he repeated to himself slowly, moving his lips. This odd habit persisted until his seventh year." (A.E. Collected Papers, Vol. 1) Maja presumably got this from their parents, and there's no reason to believe it isn't accurate. But clearly he did talk while still an infant, but in an idiosyncratic way; and it may well be that he started a little late, but not as late as legend has it.

I see the Archive article references Anthony Storr in relation to Einstein, but I wouldn't give much credence to his "analysis" of Einstein, which is little better than psychobabble. Michael White and John Gribben (*Einstein: A Life in Science*), report that Storr "diagnosed" schizophrenic tendencies, though anyone who knows anything about the manifestations of schizophrenia and is not hidebound by psychoanalytic notions would, I'm sure, reject that. Storr's reasons are rather absurd, such as Einstein's extreme distaste for authority, and that he had a poor memory for his own childhood. More plausible is the suggestion about him being somewhere along the Asberger's syndrome spectrum, but I don't think that quite works either. The characteristic feature of Asberger's is of significant difficulties in social interaction, but in his late teens and early twenties Einstein was highly sociable, made friends very easily (some of them for life) and had two close emotional attachments to girls by the time he was twenty. That does not seem consistent with Asberger's as I've seen described by those within that spectrum, and by their relatives.

My guess is that he had a slight tendency towards Asberger's, but his deciding to deal with the distracting complications of emotional involvements with other people by immersing himself in his great love (theoretical physics) was what led to his later detachment from people that is his most well-known characteristic.

Thanks for the illuminating comment!

ReplyDeleteI didn't know the thing about Einstein having a small brain was a myth. I think I remember reading that in Stephen Jay Gould's book about intelligence testing, The Mismeasure of Man, so that might be why you hear it so often; that was a pretty popular book.

ReplyDelete